The practice of meditation takes us on a fabulous journey into the gap between our thoughts, where all the advantages of a peaceful, stress-free, healthier, fatigue-free life are available, but are simply side benefits. The paramount reason for doing this soul-nourishing meditation practice is to get in the gap between our thoughts and make conscious contact with the creative energy of life itself.

---Wayne Dyer

Better not to begin. Once you begin, better to finish it.

---Buddhist saying

Death is our eternal companion. It is always to our left, at an arm's length. It has always been watching you. It always will until the day it taps you.The thing to do when you're impatient is...to turn to your left and ask advice from your death. An immense amount of pettiness is dropped if your death makes a gesture to you, or if you catch a glimpse of it, or if you just catch the feeling that your companion is there watching you.

---Carlos Castaneda

This week I caught up with an issue of Rolling Stone from December. It's the HipHop issue, and I sort of put it away as not immediately essential to my particular musical addictions. But inside, it turns out, was lurking an article that slowly has emerged as absolutely required reading. In fact, Google this morning is showing a few university courses this fall will be studying it. Military bloggers reference it too. It's about Khalid (not his real name) who spent the last 15 years fighting as a mujahideen in the name of Islam. A volunteer from his native Yemen to help drive the Russians out of Afghanistan (why? what were they doing there? guess who paid him...and what could their interest be?) Khalid recounts his story of how things changed with 9/11 and what it was like to fight Americans in Iraq. His mission, as a paid soldier, has been to help Arab countries drive foreign invaders from their soil...as he sees it. What did you say the difference is between a freedom fighter and a terrorist? And within a dozen years can these labels describe the same man? The same nation?

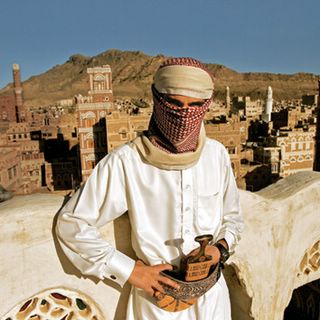

The author of the article is Tom Downey...and it's his first for Rolling Stone. An interesting guy, with apparently no political ax to grind, he made a name for himself with a book about firemen in New York a year before 9/11. Mostly he writes travel articles. There's a photo and bio here~~~ http://www.aukonline.org/?cid=1,31,46 The picture illustrating this piece is of Khalid, with ceremonial dagger.

The Insurgent's Tale

Khalid had been in Iraq for only a few weeks, but he was already sick of the place. It wasn't the missions that bothered him. He was fighting alongside a small group of Saudis, and they were consummate professionals when it came to jihad, completely focused on the lightning-fast attacks they staged each day on the foreign invaders. The ambushes usually lasted no more than five or ten minutes, but Khalid reveled in the chance to hit the streets and fire off his AK-47 at the American soldiers and their allies, four grenades strapped to his waist so he could kill himself if captured.

After the attacks, however, Khalid and the other fighters were confined to safe houses in Mosul and Haditha -- dark, dank places with no hot water or electricity. The biggest problem was the Iraqis, the very people he was there to help. Sometimes it seemed as though there were double agents everywhere, checking him out on the street, trying to overhear him speaking the Yemeni dialect that would betray him as a foreigner, all so they could pick up their cell phones and call in the Americans, maybe even collect a reward. That made this jihad more dangerous and unpredictable than the other wars Khalid had fought in -- Afghanistan, Bosnia, Somalia, places where they were often treated like heroes. When they weren't out on missions in Iraq, he and the Saudis were forced to stay in the safe house, the shades pulled down, with only a well-thumbed copy of the Koran and five prayer sessions a day to break the monotony.

Abu Musab al-Zarqawi was a pillar of strength to the insurgents. Khalid knew him from a decade and a half ago, when they were fighting the Soviets and their proxies in Afghanistan. But now, meeting al-Zarqawi in Mosul, he was amazed at the changes in his old comrade. Back then al-Zarqawi was an ordinary foot soldier like Khalid. Now, flanked by two bodyguards and barking orders with fiery determination, he was the most wanted man in Iraq, an Islamic militant with a $25 million price on his head. He had been hailed by Sheik Osama bin Laden himself as "the prince of Al Qaeda in Iraq," but al-Zarqawi still had time for a word with someone from the old days. He and Khalid chatted for a few minutes, recalling their time together in Afghanistan, before al-Zarqawi rushed off to make arrangements with an ally in Kurdistan to try to send some insurgents off to Iraq's northern mountains to fight.

That was more than two years ago, when the insurgency had been looking for fighters like Khalid, veteran soldiers who could be relied on to attack foreign troops with skill and precision. Now, back in Yemen, Khalid heard that they were looking for suicide bombers only. He would watch kids he knew signing up to go to Iraq, unaware that they were being recruited to kill themselves. It made Khalid glad he wasn't in Iraq anymore. Not that he had anything against that kind of mission -- it was a noble calling -- but he thought that a person willing to fight and die should know what he was meant to do before he left home.

At thirty-two, Khalid was beginning to have serious reservations about the course of the insurgency in Iraq. They are overkilling there. Fighting foreign soldiers was one thing -- he had been doing it all of his adult life. But did his faith really sanction killing civilians in their own country? The blood of people is too cheap. Fifteen years in the jihad, fighting in five foreign wars, imprisoned in England and Yemen, enduring the death of a close friend on a mission in Iraq -- enough. The cost was just too high. Although he was proud of all the fighting he had done in the past, Khalid wanted to settle down to an ordinary life as a father, husband and son. He was a soldier fighting a war. But what if the war had no end?

Khalid, who agreed to recount the story of his jihad on the condition that his identity not be revealed, is a Yemeni from the ancient city of Sanaa in northern Yemen. The country is one of the most lawless and drug-addicted places in the world. Despite a recent government crackdown, hand grenades are laid out alongside fresh produce at street-side markets, and sources estimate that there are at least 10 million guns in circulation in a country with a population of 20 million.

Social life revolves around qat, a leafy, reddish-green plant that contains amphetamine-like substances. Eighty percent of adult men in Yemen chew regularly, and important political and business decisions are routinely made in the mafraj, a room in many homes specially designed for chewing sessions. The leaf combines the talkative affability of pot with the drive of speed. First comes euphoria and intense sociability -- not ponderous, marijuana-induced ramblings, but a deep appreciation of the flow of conversation. In this stage, five hours can pass in what seems like ten minutes. Next comes reflective quiet -- a comfortable silence descends as people look inward, contemplating the contents of their minds. The final stage is depression and insomnia -- it's not uncommon to see solitary cloaked figures roaming the streets at night, waiting for the effects of the drug to pass. On average, Yemeni men spend about a third of their income on qat, and commerce in the leaf accounts for a third of the nation's GNP.

I met Khalid at a qat chew in the mafraj of a friend. The room was hot and stuffy, the way chewers like it, and each man in the room was identically posed: left knee up and right arm resting on a cushion. Cold bottles of "Canada" -- the Yemeni term for water, based on the market dominance of Canada Dry -- were distributed all around. The room was clean, but people were already beginning to litter the floor with leaves or stalks too thick or firm to chew. After a few hours, the middle of the room would be blanketed with a thick green carpet of discarded qat.

Qat sessions usually begin with a raucous flow of conversation. But Khalid was quiet, smiling at jokes, carefully pruning his stalks, venturing little. When he finally spoke, he told me that he had just been let out of a Yemeni prison. I asked him why.

"I was arrested as a terrorist," he told me in English, with a trace of a working-class British accent.

Late one night, he went on, an undercover anti-terrorism squad had dragged him away from his family's home in a comfortable, middle-class neighborhood of Sanaa. He was locked up and questioned repeatedly by Yemeni police in the presence of American agents. To curry favor with the Bush administration, Yemen's president, Ali Abdullah Salih, has arrested hundreds of suspected terrorists, imprisoning almost everyone who returns to Yemen with a Syrian or Iranian stamp in their passport -- prima facie evidence that they fought in Iraq. Khalid was released after thirty days when a family friend posted a large bond to ensure that he would stay out of trouble.

At this point, a friend at the qat chew hissed at Khalid in Arabic: "Why are you telling him this? Don't talk about these things."

"I have nothing to hide," Khalid told him. He then proceeded to recount the extraordinary story of his fifteen years fighting as a foot soldier in the jihad. Although it is impossible to independently corroborate every detail of his tale, other Yemenis confirmed Khalid's long, frequent absences from Yemen, his presence at training camps in Afghanistan and his imprisonment in Yemen by the anti-terrorism police. His passport contains entry stamps to Syria that match the dates he said he had gone to Iraq, and the account he gave of his arrest in England mirrors one reported by police in the U.K. around the same time. Moreover, the details Khalid gave of fighting in relatively obscure battles in Bosnia, Somalia and Afghanistan match events that actually took place. In the broad strokes of his story, at least, he appears to be telling the truth.

Khalid is not an ultraorthodox, unbending Muslim. Although he meets to chew qat wearing his Yemeni dress cut midcalf, in the style of an Islamic purist, he also wears button-down shirts and European hiking boots. He has lived in England for years and has befriended Westerners. Slight and handsome, he has the quiet charisma and modesty of the guy who is elected class president based on his low-key appeal. In short, he is not the kind of enemy we have been led to believe we are fighting. He harbors some of the same doubts that our own soldiers have about what brought them to fight and, perhaps, to die, in a place so far from home. To hear a polite and thoughtful man talk casually about his friends in Al Qaeda is to have the whole enterprise reduced to a more fragile, human scale. It is to see this war for what it is: a battle between men filled with contradictions, inconsistencies and weaknesses -- not a mythic struggle between our supermen and their ghosts.

Khalid's jihad began with a videotape he viewed at a mosque in Sanaa in 1989. He can still remember the anger he felt when, at the age of sixteen, he watched that footage of Muslim brothers and sisters being slaughtered in Afghanistan. A friend of his had died fighting there -- a martyr promised the rewards of paradise. Khalid didn't think much about his own decision to follow his friend into battle; it was the natural, instinctive thing to do. He had seen what the Russians were doing to the brothers, as Khalid calls his fellow soldiers in the holy war. His best friend had stood up to them and died. Now it was his turn.

Yemen is pious and militant, and it has supplied many thousands of the young men who have filled the front lines of jihad, fighting for their faith from Afghanistan to Iraq. The country is the ancestral home of bin Laden, whose father was a one-eyed Yemeni dockworker, and among the few people successfully prosecuted by the Bush administration on terrorism charges were the "Lackawanna Six," Yemeni Americans from Buffalo, New York, convicted of attending an Al Qaeda training camp in Afghanistan, and Sheik al-Moayad, a cleric from Sanaa convicted of conspiring to support terrorism.

There was nothing in Khalid's childhood to suggest that he would wind up joining the jihad. His father was a moderate Muslim with a steady job as a civil servant in the Yemeni government. Khalid worried that he wouldn't be able to get a passport or leave the country without his father's permission. But the recruiters for the Afghan war were acting with the support of the Yemeni government, and within a few weeks, whether or not his father liked it, Khalid had a brand-new passport stamped with a visa for Pakistan.

The final hitch was that a close relative of Khalid's worked at the Sanaa Airport. Khalid feared that an airport clerk might recognize him and alert his family. The recruiters got around that by driving him directly onto the tarmac. Khalid climbed aboard the plane to Pakistan without even passing through immigration.

The reality of jihad, Khalid quickly discovered, was very different from the images presented on the videotape. When he finally made it into Afghanistan, he spent his first night near the front. That evening, a soldier who had been killed was brought back for burial by the mujahideen. Khalid didn't know the man, but seeing his body terrified him. "I'm scared," he told a friend. "I just want to go home."

"Everybody feels like that at first," his friend said. "But soon you won't be scared."

Khalid fought in Afghanistan for two years. He learned to use his weapon, to fight, and to pray with the precision and punctuality of the Salafis, the Islamic purists who were driving the holy war. It was a harder, less forgiving kind of Islam than he had known in Yemen, but its rigidity gave him the strength and discipline he needed to survive as a homesick kid at war in a foreign land. He had arrived in Afghanistan at a pivotal moment. The war against the Soviets was giving birth to a new breed of Arab fighters known as "Afghan Arabs." It was there that the seed of allegiance was planted for the thousands of young men who had flocked to the mountains of the Hindukush to help fight the communists. Afghanistan represented the birth of the global struggle. By helping defeat a superpower, the jihadists showed the world the power of Islam. And in the decade that followed, they would spread that war to the rest of the world.

In 1993, after Khalid had returned home from Afghanistan, he began to hear about a war in Europe where Christians were slaughtering Muslims. Stirred by the stories, he went to join the fighting in Bosnia. Again, as in Afghanistan, he was on the side the world viewed as the good guys -- the Bosnian Muslims who were the victims of relentless "ethnic cleansing" at the hands of the Serbian nationalists led by Slobodan Milosevic. The combat was much more intense than the action he had seen in Afghanistan, where the Soviets used superior firepower to bomb them from a distance. In Bosnia, the enemy was right in front of you, and you had to kill or be killed each day. Khalid fought alongside a group called the Green Berets, named not after the American Special Forces but after the color of Islam.

One day, after a year at war in Bosnia, Khalid was on the front line between Tuzla and Zenica, battling Serbian snipers who were shooting into Muslim villages from a nearby mountain. Suddenly, he came face to face with a Serb. The Serb got the jump, firing seven bullets into Khalid's stomach. Bundled up in heavy winter clothing, Khalid at first couldn't even tell how badly he was hit. When he started to peel off the layers around his stomach, part of his guts leaked out into his hands. He stuffed whatever he could back in and lay down on the ground. When a Saudi brother managed to drag Khalid beyond the reach of the Serb snipers, it took three injections of morphine to quiet his screaming. "You must be a heavy drinker," said the medic from Bahrain who administered the shots.

"No," Khalid said. "I chew qat." The medic, who had never heard of the plant, thought Khalid was hallucinating.

It took hours to carry Khalid down the mine-covered trail. When he finally arrived at a triage area at the base of the mountain, he was put with a group of those too far gone to save and left to die.

Soon after, the medic who had given Khalid the morphine arrived and began searching for his patient. He found Khalid lying among the rows of the dead and ordered a Bosnian army helicopter to speed Khalid to a hospital, where he woke up in pre-op. For six months he lived off an IV tube, his intestines hanging outside his body in a sterilized bag. He shrank to skin and bones -- under seventy-five pounds -- until he looked like "an African famine victim." The hunger was so intense, he would claw at his own stomach.

On his way to Saudi Arabia for further surgery, Khalid stopped home in Yemen. When he arrived at the airport in a wheelchair, his father slapped him across the face. "This is all your doing -- tell Sheik Zindani to help you now," he said, referring to a firebrand cleric who had urged Khalid to go to Bosnia. But Khalid received a warmer welcome in Saudi Arabia, where people from all over the country visited him in the hospital, leaving gifts of flowers, perfume and money for a man they considered a hero.

It took Khalid several years to recover from his wounds. In 1996, he joined a group of Arab fighters going to Kosovo, where Christian Serbs were once again menacing a Muslim minority. By the time he arrived, however, the Serbs had already sealed off the country, making it impossible for him to enter. Unable to join the jihad, Khalid decided to move to England, where many of the brothers had settled.

England is the home of one of the largest concentrations of Yemenis in the world; parts of Yemen were long ruled by the British, and thousands of Khalid's countrymen have settled there. When Khalid arrived, he went to see a Palestinian cleric he knew, who helped connect him to the Yemeni community. Khalid settled down to work at a corner store, chewing qat all day while manning the register. The leaf is legal in England, and Khalid's store stocked and sold qat to Yemenis in the neighborhood.

Khalid was twenty-three. For the past seven years, he had been fighting in battles all over the world. He had never been on a date, never kissed a girl, never really talked to a female who wasn't a close relation. So he did what many a lonely guy does when he's stuck in a city he doesn't know very well: He fell for the waitress at the coffee shop.

She was of Irish descent, and she smiled every time she brought him his coffee. Khalid went to a Yemeni friend and explained his quandary: He was in love, but he didn't know what to say.

"No problem," the friend told him. "I'll ask her out for you."The waitress was receptive but confused. "I like him," she told the friend. "But why doesn't he just talk to me himself?"

Things were rocky from the start. On the first date, she wanted to go to a disco, but Khalid refused. Outside a restaurant, he grew angry when a passing man looked at her. "What are you going to do if I walk on the street with you?" she asked. "Fight everybody in the city?"

A couple of dates later came the gifts: three bottles of pricey perfume and a ring -- the ring. He could barely get the words out in English: "I want to marry you."

"Marry me?" She was surprised, amused even. "What's my name?"

"It's hard for me to remember it," he stuttered.

He gave her a week to decide. His gallantry must have won her over, because they were married within a month.

Right after that, the misery began. Khalid tried to control her and force her to wear the hijab, the head scarf worn by devout Muslim women. Their arguments were so loud that neighbors knocked on the door and banged on the walls. He realized the way he treated her was wrong, but he didn't know any other way. They separated, and Khalid got a British passport out of the marriage.

Khalid returned to the only life he knew. This time, his destination was Somalia, where a radical Muslim faction was attempting to impose strict Islamic law, known as sharia, on the entire country. Posing as a Red Crescent worker, Khalid bribed a pilot to fly him from Nairobi to the Somali town of Luuq, where he delivered $40,000 in cash to a Somali warlord allied with the Islamic faction. The money was from Arab backers, mostly Saudis, who were using their disposable income to influence the many conflicts that plagued Africa and the Middle East. Their cash not only advanced the cause of Islam -- it also bought allies who might help the struggle in the future.

There were forty Arab fighters in Luuq helping to fight the Ethiopian army, which regularly attacked from across the border. The longer Khalid stayed, the more dire conditions grew. At times the insurgents survived only by eating pure sugar. The brothers eventually organized a counterattack and retook the city. Khalid fought for two days straight, until he and his men ran out of ammunition. Reduced to throwing stones, most of the Arab and Somali fighters were killed. At one point the few remaining survivors were so desperate, they started to dig their own graves.

Khalid escaped, badly shaken but alive, with neither the money nor the means to get home. What do you do when you're on jihad, all the money's run out and you just want to leave? For Khalid and his remaining men, their only chance was to try and get a piece of the forty grand that Khalid had already delivered to the warlord.

"I can't help you," the Somali leader told him. "We need all that money for our fight."

Khalid wasn't a high-school debater; he was a holy warrior, so he did what came naturally: He put a loaded gun to the man's head. "I'll kill you or you'll help us get out of here," he said. "We brought you $40,000. Now you need to help us." The warlord was convinced. Khalid and his fellow insurgents eventually escaped to Yemen by crossing the Gulf of Aden on a dhow packed with goats.

When Khalid finally arrived home, his father was furious. "What the hell happened to you?" he demanded. "Where did you come from?" To calm him down, Khalid promised to stop fighting and start a normal life. But whenever the call came, he answered. In 1999, Khalid traveled to Tbilisi, in Georgia, and tried to get into Chechnya, where the Russian army was slaughtering Muslims. But many mujahideen, he learned, had died trying to walk across the mountains to Chechnya. Khalid was willing to die fighting for his cause, a gun in his hand, but freezing to death on a mountaintop was no way for a soldier to give up his life. He headed back to England, returning to his job as a clerk at the corner store, chewing qat to keep himself alert, always on the lookout for the next opportunity.

In 2001, he got a call from Afghanistan. The brothers wanted him there.

When Khalid arrived in Afghanistan early that year, the Taliban had unified most of the country under the strict banner of sharia law. The ragtag bands of foreign jihadists who had fought the communists were gone. In their place was a sophisticated network of training camps run by Al Qaeda. This was a new age of jihad, a well-organized, well-financed struggle led by Osama bin Laden. Jihad, Khalid discovered, had been institutionalized.

At first, Khalid ran a sort of hostel in Mashhad, deep in the rugged Iranian frontier. The 600-mile-long border between Iran and Afghanistan is difficult to police because of its steep mountains and many trails, and Al Qaeda was taking advantage of the covert passageways, sheltering jihadists at Khalid's hostel before sending them over the mountains into Afghanistan.

That summer, on a trip into Afghanistan, Khalid met bin Laden at the leader's camp near Kandahar. They talked about the course of jihad and the situation in Yemen, a country for which bin Laden had a special fondness -- his father and one of his wives were born there, and Yemen had always supplied some of the best and bravest mujahideen, men bin Laden relied on as his most trusted fighters and bodyguards. Khalid thought jihad should be extended to Yemen, but bin Laden disagreed, saying it would stretch his forces too thin. "There is no justice in Yemen," he told Khalid, "but we can't fight there now."

By the summer of 2001, there was a palpable feeling in the camps that something big was about to happen. Around that time, Khalid ran into an old friend from his days in Bosnia: Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, a Pakistani who had risen to prominence as an operational chief of Al Qaeda. Mohammed asked Khalid to volunteer for a mission to the United States or Europe -- his British passport would enable him to slip in and out of a Western country. But Khalid refused. He was willing to fight foreign soldiers invading Arab lands, but he wasn't ready to take the war to America or Europe.

On September 11th, Khalid was near Kabul when a Libyan cleric announced that the World Trade Center had been destroyed. Everyone in the camp exploded in jubilation -- the mood was exhilarating, insane, like Mecca at the height of the hajj. As Khalid remembers it, it was the moment when everything changed. The mujahideen had struck a blow against the West that would never be forgotten. And in the process, they had made themselves the target of the world's only remaining superpower.

When the United States invaded Afghanistan, Khalid saw his most intense fighting in and around Khost. Even with help from a local sheik, the foreign fighters couldn't do much against the American onslaught. One night, Khalid was sleeping in a car near Khost with three other fighters. When he woke up and walked away to relieve himself, the car was blown to bits. Khalid later helped to bury a body he believed to be the wife of Ayman al-Zawahiri, bin Laden's second in command. The woman had been killed in a school where many Al Qaeda families had sought shelter from the American bombings.

After a few weeks, as the relentless bombing continued, a message arrived from bin Laden: Any mujahideen who could still travel should return to their home countries. There was no point in dying in Afghanistan. "There was no way to fight a decent war there with the Americans," Khalid recalled. "We hardly ever saw a soldier to fire at." Though the Bush administration believed it had routed the Islamic forces, the mujahideen, in fact, had beat a strategic retreat. American commanders, reluctant to expose ground troops to danger, had relied on a strategy of bombing from above that allowed many Al Qaeda members to slip away, ready and willing to fight again another day.

In late 2001, Sheikh Mohammed, the Al Qaeda operational chief, ordered Khalid to guide a group of fifty women and children to safety in Iran, over the same mountains he had crossed to enter Afghanistan. "You know the route," Mohammed said. "Take some families with you." He gave Khalid thousands of dollars to pay for Afghan guides and to take care of the Iranian border guards.

The journey to Iran took two weeks. They trekked across high mountains -- a string of women and children wandering through a remote corner of the world, eating dates, plants and whatever animals they could kill along the way. When they reached Iran, pro-Taliban allies were waiting to shuttle them to safety. For weeks after the trip, Khalid's shoulders ached from carrying so many children on his back.

In the years before September 11th, Khalid and his fellow mujahideen could move around the world with relative ease -- creating fake passports, bribing border police, claiming that they were Iraqi dissidents fleeing the tyranny of Saddam Hussein. Immigration officials were a nuisance, but there was always a way around them. Now, returning to England from Afghanistan in 2002, Khalid discovered that even a real British passport couldn't protect him from scrutiny. When he changed planes in Abu Dhabi, the police stopped him, suspecting that his passport was fake. A well-dressed supervisor came out to question him. "What's Marks and Spencer?" the man asked.

"A big British department store," Khalid said. "Look, I'm a British citizen, from Yemen. I'm Shiite. Why would I want to go and help the Taliban? They hate Shiites. I was on a pilgrimage to holy places in Iran." After a few hours they let him go, and he boarded a plane to London.

At Heathrow, he was detained again. British officials asked for his luggage and he told them he had only hand baggage. Strike one. They examined his ticket: one-way from Tehran. Strike two. As he sat on a hard bench in a glass-paneled interrogation room, deathly afraid, he could see officials leafing through his passport in the next room. They kept coming back to one page -- a page that had been doctored in Afghanistan to remove a Pakistani visa. He claimed he had accidentally left it in his pants and then ironed them, but they didn't buy it. Strike three. At midnight the agents handcuffed him, shoved him in the back seat of an unmarked car and took him to a maximum-security detention facility.

They questioned him for five days. As the interrogation continued, however, Khalid came to see that he was safer in England, protected by the country's due-process laws, than many of his brothers detained by the Americans in Afghanistan. Realizing that the police had nothing on him, he denied everything. They finally let him go, unable to hold him without further evidence.

The incident communicated something important to Khalid: The jihadi's life had changed after 9/11. Not long ago he could travel all over the world with impunity; now they were hassling him at Heathrow just because he was flying in from Tehran on a one-way ticket with a piece of hand luggage.

Khalid lived quietly in England for a year and a half, working at the corner shop and praying at a local mosque. Around that time, he befriended a fellow Yemeni who would come to share his passion for jihad: Wa'il al Dhaleai, who was well known in England as a leading tae kwon do instructor and Olympic hopeful.

In 2003, when the U.S. invaded Iraq, it was clear to Khalid where he would next do battle. Getting into Iraq from Syria was no more difficult than dressing up like a farmer and walking across the border with phony papers in the middle of the night. But the fighting was a different story. In the early stages of the war, there weren't many foreign fighters like Khalid in Iraq; the bulk of the insurgency was comprised of native-born Sunnis who simply wanted to drive the Americans from their country. They welcomed the foreigners -- they weren't in a position to be choosy -- but they weren't interested in jihad's broader goal of imposing Islamic law on Iraq.

Khalid quickly discovered that it was impossible to blend in -- Iraqis tend to be bigger than Yemenis, and their body language and dialect are hard to imitate. Shiites were especially quick to report foreign Sunnis to the authorities. Khalid and his Arab brothers had the same problem as the American forces they were fighting: They didn't know which Iraqis they could trust.

Most of the foreign fighters in Iraq were very young. At thirty-two, Khalid felt like an old man. Stuck in their safe houses, the mujahideen had to rely on Iraqi insurgents to report on the movement of American convoys, scouting for an opening that would allow them to attack. Months after President Bush declared "mission accomplished" in Iraq, Khalid was ambushing U.S. forces in the northern city of Mosul. Around the same time, Saddam Hussein's sons died in a fierce gun battle there. That October, Khalid's friend Wa'il also died, fighting the Americans in the town of Ramadi.

After three months in Iraq, Khalid returned to England through Syria. But jihad seemed to shadow him everywhere. One evening, after returning home from work, Khalid heard a helicopter overhead. Seconds later the police kicked in the door, handcuffed him and arrested him on suspicion of terrorism. People on his block couldn't believe that the friendly guy who sat behind the counter at their corner store was an Al Qaeda fighter.

The agents interrogated Khalid about his past. They knew he'd been in Syria. Business, he explained. They knew he'd been detained in 2002 after returning to England from Iran. Shiite pilgrimage. I've never been in Afghanistan. I don't want to go. They knew there were Yemeni fighters being held in Guantanamo who said Khalid had recruited them to train in Afghanistan. Liars. They knew he had spoken on his cell phone to Wa'il, shortly before his friend had died in Iraq. Just a chat.

After Khalid spent a week in prison they let him out, just like they always did. They didn't have enough evidence to keep him. When he was released, his next-door neighbors, mostly white Britons, were there to welcome him home. "I might doubt my own son," one old man said, "but I'll always believe Khalid." Most of the Yemenis and other Muslims who had been Khalid's friends had deserted him when he was arrested, fearing for their own safety. When he saw his British neighbors standing by him, Khalid couldn't help bawling.

After the arrest, Khalid returned to Iraq for two more months in 2004, in part to honor the memory of Wa'il. Living in safe houses, he once again went out on raids against the Americans. The heaviest fighting he saw was in Al Qa'im, where thirty Arabs and more than a hundred Iraqis fought for a week against the Americans. Khalid saw seven brothers killed, mostly from Syria and Saudi Arabia. He believed the insurgents killed about ten soldiers from the other side.

By this time, however, the nature of the insurgency had changed. Al-Zarqawi had succeeded, for the moment, in taking over the homegrown resistance. Many of Saddam's former secret police and Republican Guard were now integrated into cells with jihadists like Khalid. The leadership of Al Qaeda had financial resources and strategic expertise that the Iraqis lacked, and the foreign fighters were more willing to die than the local Sunnis -- and more willing to kill civilians.

Disturbed by the killings, Khalid began to rethink the role of jihad in his life. Would his faith really justify killing his British neighbors in their own country? Would he ever be able to live a normal life? Hearing about Yemenis he knew who had disappeared into the gulag at Guantanamo, he feared he could end up in prison for life, a fate he considered worse than death.

The doubts intensified after he returned home to Yemen and was arrested earlier this year. "Enough is enough," his father implored. "It's time to settle down and stop this stuff." After Khalid was released from prison, he and a group of other Afghan Arabs -- the blanket term for those who fought or trained in Afghanistan -- were summoned to a meeting with Ali Abdullah Salih, the president of Yemen, who was trying to contain the jihadists. In private, Salih called them "my sons" and said he had been pressured by the Bush administration to crack down on them. He also did something seldom acknowledged in the war on terror: He offered to pay them off to stop fighting.

"We will help you get jobs, get married," Salih told the men. "Write down your name and what you want."

Khalid didn't take the money, but he was tempted by the offer. He wanted out of jihad. On a trip back to England in late 2004, he had proposed to a Muslim woman he met through friends. In August, his fiancee and her family visited him in Yemen. He was visibly excited about the prospect of settling down and starting a family. He and his betrothed would go on heavily chaperoned picnics to a park outside Sanaa with their extended families, or visit the home of a close relative. They have never been alone together, and he has never seen her face.

But Khalid can see no way to escape from his past. Like many veterans, he looks back on his years of fighting with nostalgia -- the thrill of battle, the feeling of brotherhood, the steadfast devotion to a cause. But on some days, it feels as if he has no place in the world. He lives in Sanaa, but it no longer seems like home. Every few days he walks down to a storefront calling center and phones his brother in England. He doubts he can ever go back to the life he knew there. He often visited the mosques frequented by the London bombers, and he fears police will arrest him if he tries to return. But if he stays in Yemen, the brothers will keep trying to draw him back into the struggle.

These days, when they come over to his house and try to rally him for a mission to Iraq or Sudan, Khalid looks bored and says that he can't go anywhere now, that it would put his family in Yemen at risk. Even his fiancee's younger brother tried to enlist his aid to join the insurgency in Iraq. Khalid told him he couldn't help. He doesn't want any part of the fighting, but uncertainty might be seen as betrayal. So he keeps silent, and waits, and imagines the day when the war, and all that comes with it, will finally end.

TOM DOWNEY

Posted Dec 05, 2005 12:48 PM

©Copyright 2006 Rolling Stone

http://www.rollingstone.com/politics/story/8898175/the_insurgents_tale/