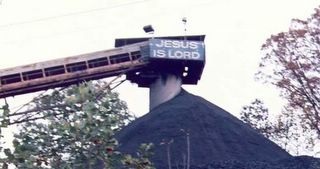

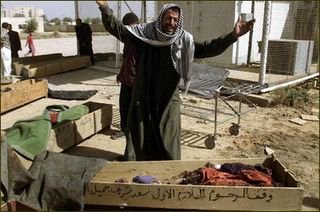

Mary Hufford took this photograph of mountain top removal. This and others are at the Library of Congress site Tending the Commons: Folklife and Landscape in Southern West Virginia. http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/collections/tending/

When a thing is funny, search it carefully for a hidden truth.

---George Bernard Shaw

Searching for words, hunting for phrases, when will it end?

Esteeming knowledge and gathering information only maddens the spirit.

Just entrust yourself to your own nature, empty and illuminating---

Beyond this, I have nothing to teach.

---Bankei

Dying cricket,

His song so full

of life.

---Basho

One of the first questions people ask when they move to a mining area of the Appalachians---or even just drive through mountains of West Virginia, Kentucky, Pennsylvania, Ohio---is "What's happening over there?" They're referring to a startling bare spot on the horizon, out in the middle of nowhere, no towns around, maybe a big crane thing sticking up. What you're seeing is called strip mining or mountain top removal, and the little part of the machine inadvertently visible from the highway might be something like The Big Muskie, which was the largest mobile land machine in the world http://little-mountain.com/bigmuskie/ . It would take a stack of books to describe the history of coal mining and its effect on the lives of the people here---and certainly other regions of the Earth too---but did you know that history continues? Mining goes on here, providing jobs and taking them away, with mountain folks wrestling the same issues they've had to deal with for 200 years.

A great warrior and inspiration to me is Elisa Young, who lives among the coal-powered electric plants around Racine, down on the Ohio River. That's just a couple dozen miles and around a few riverbends from Cheshire, the town American Electric Power BOUGHT rather than clean up their stacks to remove the toxicity that brought poison to the lives of people who used to live there---and toxic rain to the Adirondacks. She's down there going to public meetings and hearings day and night, and reports on her work (all sparetime, as she has a regular job) at a Sierra Club website our local group maintains.

Earlier this week she posted an editorial I'd like you to read. It appeared in the Lexington Herald-Leader on Monday, and was written by Erik Reece, who teaches writing at the University of Kentucky, and wrote a piece called "Death of a Mountain" in the April Harpers Magazine~~~

Coal companies' damage easy to see

By Erik Reece

Bill Caylor (President of the Kentucky Coal Association), in his latest apology for the damage that large coal corporations are inflicting on Eastern Kentucky, claims that while pessimistic editorialists never change, the coal industry has. Certainly no one is getting gunned down in the streets of Matewan anymore. But how much has the industry changed?

Ask Larry Gibson, who, because he refuses to sell his mountaintop homeplace, has seen his cabin set on fire, his two dogs shot and his solar panels sabotaged.

Ask Judy Bonds and Bo Webb of Coal River Mountain Watch, who received death threats last month because they dare to criticize the industry.

Ask Patsy Carter, who, after her daughter was killed by an overloaded coal truck, began speaking out. Since then, she has had 22 flat tires. At night, she can hear nails hit her mailbox as coal trucks speed by.

I have met a whole lot of decent people in the coal industry. But despite corporations' legal right to operate as "persons" under the law, a corporation is not a person. And as the 2000 Martin County disaster showed, corporations often operate without the moral compass that we hope will guide individuals.

How else can one explain why, over the last four years, 65,000 coal trucks have left Massey Energy's treatment plant in Sylvester, W.Va., and, according to an internal document, every single one was illegally, dangerously overloaded.

To look at the eastern coalfields on an aerial map and to see the black scars left by mountaintop removal is like looking at the X-ray of someone suffering from lung cancer. Caylor asserts, correctly, that only "7 percent of all of Appalachia" has been mountaintopped. But what if 7 percent of someone's lung was cancerous, and a doctor said there was no need to treat it?

"But won't it spread?" asks the patient.

"Of course it will," the doctor replies.

"But shouldn't we stop it?"

"Nope. Keep smoking. It's good for the cigarette industry and good for our economy."

I don't evoke this sad analogy lightly. Strip mining is destroying life in the streams of Appalachia and, as an Eastern Kentucky University study of Letcher County found, that polluted water is causing cancer and many other serious health problems throughout the region.

Without serious state or federal intervention, mountaintop mining will continue to spread havoc across Eastern Kentucky.

Caylor asserts that coal mining supports 14,000 jobs in Eastern Kentucky. But according to the Kentucky Coal Association's own Web site, only 5,237 of those jobs are on surface mines. That's about 100 jobs for each Appalachian county in Kentucky. Is destroying entire watersheds -- their trees, their water, their soil, their people -- worth 100 jobs?

"It's the lack of jobs that creates poverty," Caylor writes. It sure is, and it is the increased mechanization of the coal industry over the last few decades that is directly responsible for the lack of jobs in Eastern Kentucky.

It is no coincidence that the counties that have seen the most strip mining remain the poorest.

Caylor is right about one thing, though. We should retire the phrase "act of God" when talking about the damage caused by mountaintop mining. The floods and mudslides that, over the past five years, have killed 14 people who lived under strip mines in southern West Virginia were clearly acts of man. The only act of God was the creation of the Appalachian mountains -- the most biologically diverse ecosystem in North America.

Genesis 2:15 says that the creator put human beings on the Earth "to work it and take care of it." But we have been very poor stewards of the creation, and there may be hell to pay.

But because Caylor says that opponents of strip mining never have a "vision for the future," I want to offer one in the form of the Appalachian Regional Reforestation Initiative.

Paul Rothman and Patrick Angel from the Office of Surface Mining have been encouraging coal companies to reclaim strip jobs with the kinds of trees that the bulldozers unearthed.

There is so much abandoned mine land in Eastern Kentucky right now that a tree reforestation program, funded by the state's severance tax, could reduce the region's unemployment rate to zero. Erosion and flooding would decrease, carbon sequestration would increase and Eastern Kentucky would finally have a wood-products industry that might bring an end to the ugly legacy of coal.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

© 2005 Lexington Herald-Leader and wire service sources

http://www.kentucky.com/mld/kentucky/news/editorial/13375607.htm

Erik's Harpers essay, with photos, is preserved here http://www.wesjones.com/death.htm

Elisa added the following in her post~~~

"Thought I would forward this and say the violence is not exaggerated.

"Larry called me one night about a month ago when he dropped a friend of ours off after they'd been out to speak against on MTR (mountain top removal), and her husband was waiting for her - with a pistol. He called to ask me to find out what kind of trouble they were having.

"Halloween they tried to burn Maria's footbridge to her home in the hollow while I was on the phone with her and she had to leave to run and put the fire out. If she loses her bridge it's a one mile walk back into the hollow and a half mile down the hill, and they are carrying in all of their drinking water since MTR started. The estimate to install city water is over $30,000. They don't have that kind of money and the coal company refuses to take responsibility."

People who live in the mountains around here tend to be fiercely independent, trying to sustain their lives without receiving charity from anywhere. You can't depend on government benefits because the next election may wipe them all out. So they garden a little bit, gather herbs and roots, barter, make crafts and moonshine, and grab jobs when one comes around. It's a rough life, but they think living in the mountains is worth it. Mountain top removal? I heard one guy say, "Hey, the top is the best part!"