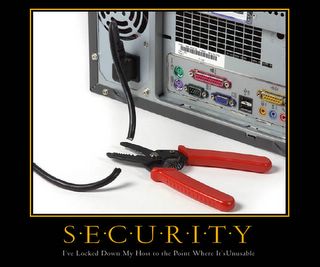

The image accompanying is from a 2004 calendar entitled A Year Of Agony, which was put out by Sourcefire, a network security company. http://www.sourcefire.com/ The caption reads "I've locked down my host to the point where it's unusable."

Jump into salvation while you are alive. What you call "salvation" belongs to the time before death.

---Kabir

To be enlightened is to be intimate with all things.

---Dogen

God whose love and joy are everywhere can't come to visit unless you aren't there.

---Angelus Silesius

Our computer is the same one we had in 2004 (we're window-shopping eagerly for a new one) but in the meantime has developed so many knots in its processing that I feel we're losing this war almost as badly as the invasion of Iraq. For indeed what other appliance do you buy for your household that comes under actual attack from parties known and unknown the moment you connect it up to use? Say what you will about the malicious geeks out there, they're brought planned obsolescence to an art form. Of course neocons preach the consumer needs no help battling this army all by yourself in your tilty deskchair.

I spend at least a half hour a day doing routine maintenance on this thing. We have dialup but I can't blame all the weirdness in the machine on that. I've been struggling for 2 months to get my Norton scan to work properly again. I suspect a Microsoft Priority Update as the culprit...but maybe it's an undetectable worm picked up at MySpace. I seem to be spending more time worrying about what's infecting our computer than my own bodily health! But like that organism, it seems the more I try to do about it, the worse everything gets. Thus the illustration here.

Time Magazine has designated "YOU" as Man or Person of the Year...and the reason for that is how much time "you" spend on your computer and how blogging is affecting the world scene. Frank Rich has his opinion on that choice---and does a little review of other media we've been watching, including YouTube---in his Christmas Eve column. As usual blogger Rozius Unbound has posted the article for us. Heh heh. http://roziusunbound.blogspot.com/2006/12/frank-rich-yes-you-are-person-of-year.html But for the real scary scoop on that "personal" computer and what monsters may be inside, you have to go to PCWorld's review of Security Issues in 2006, just posted a few hours ago. Hot off your hard drive (and don't forget to clean that fan in the back occasionally) is the news you've been afraid is hitting you from all sides~~~

http://www.pcworld.com/article/id,128234-c,techindustrytrends/article.html

Happy New Year.

2 comments:

While I'm dealing with replies I received zapping Norton as the good guy I always thought it was and patiently awaiting a promised callback from the company's management, here's the referenced article to preserve at this entry~~~

2006: The Year in Security

Online attacks, spam, and sneaky cybercrime top list of year's most common security issues.

Jeremy Kirk and Robert McMillan, IDG News Service

Tuesday, December 26, 2006 12:00 AM PST

Though Internet-crippling virus attacks now seem to be a thing of the past, PC users didn't feel a lot more secure in 2006. That's because online attacks have become more sneaky and professional, as a new breed of financially motivated cyber criminals has emerged as enemy number one. Microsoft patched more bugs than ever and whole new classes of flaws were discovered in kernel-level drivers, office suites and on widely used Web sites. Vendors' chatter about security is at an all-time high, but the bad guys are still finding lots of places to attack.

And, oh yes, spam is back.

Following are five of the top computer security stories in 2006.

Cybercrime Dividends

Hackers teamed with professional criminal gangs in increasingly sophisticated computer crime operations aimed purely for profit.

Much of the trouble centered on phishing, a type of attack where fake Web pages are constructed to harvest log-in details, credit card numbers or other personal information. Credit card numbers are often sold online to others for illicit gain. http://www.pcworld.com/article/id,127799/article.html

In May, 20,000 phishing complaints were reported, a 34 percent increase over the previous year, according to U.S. Department of Justice report. The U.S. hosts the largest percentage of phishing sites, it said.

But law enforcement agencies are getting more organized and cooperating better, particularly in international investigations. At least 45 countries participate in the G8 24/7 High Tech Crime Network, which requires nations to have a contact available 24 hours a day to aid in quickly securing electronic evidence for trans-border cybercrime investigations.

The private sector has also helped. Microsoft filed dozens of civil suits and gave information to law enforcement for criminal cases in Europe, the Middle East and the United States against alleged phishers throughout 2006.

It's a Brand New Day

With automatic software updates now the norm, hackers have been forced to look a little harder for ways to put their malicious software on unsuspecting victims' PCs. In 2006 they turned to zero-day attacks as never before.

These attacks take advantage of previously unreported flaws in software, and in 2006 they became a top concern, according to the SANS Institute. In fact, hackers kicked off the new year in 2006 by releasing zero-day attack code based on a flaw in the way Internet Explorer handled WMF (Windows Meta File) documents. http://blogs.pcworld.com/staffblog/archives/002851.html

This was followed, later in the year, by a rash of very targeted online attacks that exploited unpatched flaws in Microsoft's Office software. In fact, Microsoft warned of the latest such attack -- this one targeting a flaw in Word -- just this month.

To underline the scope of the zero-day problem, security researchers launched widely publicized "Month of Kernel Bugs" and "Month of Browser Bugs" projects, during which they exposed a new, unpatched vulnerability in browsers and operating systems every day for a month.

Spam Avalanche

Microsoft's Chief Software Architect Bill Gates predicted two years ago that spam would be gone by 2006. He should check his in-box.

Rising volumes of junk mail nagged IT administrators throughout 2006. Up to 90 percent of all e-mail was spam, depending on the vendor recording the statistics. Spammers found creative ways to circumvent security software. Image-based spam, where individual messages appear to be unique by subtracting or adding pixels, foiled some security techniques. http://www.pcworld.com/article/id,127801/article.html

Spammers also put messages in the images themselves, a tougher challenge to stop since it requires processor-intensive optical character recognition (OCR) techniques. Spam remained the delivery vehicle for other malicious software such as keystroke loggers and rootkits in addition to promoting links to phishing sites, which often aim to steal financial data or log-in credentials.

Web 2.0 Gets Hacked 1.0

MySpace.com may be a poster child for Web 2.0, but from a security perspective, it hasn't been looking so pretty.

That's because the popular social networking site was hit hard by a password-stealing worm that exploited a scripting vulnerability on the Web site. And this was not even the first worm to hit MySpace. In October another more benign worm, called Samy, automatically added a Los Angeles teenager's name to visitors profiles, quickly making him appear to be the most popular member of the MySpace community. http://www.pcworld.com/article/id,128074/article.html

Security experts say that the kind of cross-site scripting attack used in the recent MySpace worm has become much more prevalent in the past year, as hackers have discovered just how much can be done with these attacks. These bugs can be used to do far more harm than many people realize, security experts say, including forcing PCs to download illegal content, hack other Web sites or send e-mail.

Vista Lockout Irks Vendors

Microsoft rankled security vendors by saying it wouldn't allow their software to access the kernel of the 64-bit version of Windows Vista. Patch Guard, Microsoft's kernel security technology, blocks access to prevent unauthorized modifications by malicious software.

Vendors, led by Symantec and McAfee, argued they needed access to the kernel to detect malicious software such as rootkits, which burrow deep into the OS. After a flurry of public statements and pressure from the European Commission, Microsoft agreed to make APIs (application programming interfaces) available.

The APIs will allow host intrusion prevention technologies used by vendors to function without hooking the kernel. But Microsoft said the APIs wouldn't be ready until the release of Service Pack 1 for Vista.

The unholy wits at a site I frequent often mocked out those of us who suggested improvements to the site (back in the day when the Webmaster actually visited the twisting hallways once in a while). They all agreed a message board is the Wild West and the only real decision-making is arrived at by shootout. (One bounced member got his in rather more of a dead-of-night assassination.) On Christmas Eve, the LATimes published an article that reveals the whole Web revels in neocon manipulation techniques. Read it and weep...or rejoice, depending on how handy you are with weapons~~~

The wild, wild Web

Getting to No. 1 on the Internet is a game rife with sleight of hand. But smart new tools might just change the rules.

By Reed Johnson

Times Staff Writer

December 24, 2006

If you go searching for God on Google, here's the first thing you're likely to find: a video essay titled "The Interview With God," which serves up a breezy Q&A with the Author of Creation punctuated by New Age-y piano riffs. (Spanish speakers making the digital pilgrimage will get, as their No. 1 search result, an invitation to a gig by a Hawthorne band called "Dios.")

Why "The Interview With God" and not the Book of Job or the Bhagavad-Gita? Because Google's busy little algorithmic brain tends to give priority to websites that link to the most other sites with similar content, and satisfy other mystic criteria known only to Google's inner circle of geeky utopians.

It may well be that "The Interview With God" reached its lofty perch because it's profound, or at least profoundly popular. But at this point in the Web's evolution, it's no stretch to guess that, the site's merits aside, someone connected with it probably knew how to, ah, finesse the Web's search-engine mechanisms.

For one naive, shining moment in the '90s, the assumption was that on the Web, popularity would be democratic, earned one enthusiastic click at a time. Pure. Simple. Untainted by Billboard, Hollywood, Nielsen or other mainstream media usual suspects. But that was before clicks meant cash, and before a flood of tools and communities brought millions of new, mainly nonprofessional content providers online, jostling to get their videos watched, audio clips downloaded and blogs and Web pages linked to bigger, more popular blogs and websites.

This intensifying contest has stoked the imperative to be "most viewed," "most e-mailed," "most played." And that, in turn, has led to a gamut of strategies for one-upping the competition.

Today, the name of the game is gaming the system. And there are so many ways to do it that, whether it's your son's alleged number of MySpace "friends" or a confab with the Almighty, if the ranking is inordinately high, a certain amount of caveat emptor is probably called for.

Over at YouTube there were accusations this year that certain videos were pushed up most-viewed lists by viewers using fake account names. Spammers keep finding ingenious ways to clutter up our e-mail in-boxes by using code words that do end runs around filters. One site launched pop-up windows, then counted them as hits.

Then there's "Google bombing" or "Googlewash," in which individuals or groups (say, members of a political party) attempt to boost their own Web page rankings, or else discredit their enemies by linking and cross-linking them to negative sites (which is why, for the last two years, a search for "miserable failure" has turned up a bio of George W. Bush). Some Wikipedia entries are periodically sabotaged — that is, rewritten — by so-called "trolls" with ideological axes to grind.

A cottage industry has sprouted up around "search engine optimization," more commonly known as boosting Google rankings. The trick: seeding a website with key terms that will show up in text hyperlinks, regardless of the site's actual importance or relevance. And there's always the fallback of enlisting actual humans to help click you up the list.

All this just compounds the endless, everyday flow of disinformation, evasion and falsehood abetted by one of the Internet's defining features: users' ability to disguise their identities. Thus, would-be Hollywood ingénues impersonating real-life teenagers (see: Lonelygirl15 and her ersatz video diary), and any number of creeps or bored kids posing as Brangelina look-alikes on Internet dating services.

Blame ourselves

But if the Web has failed to live up to some of the Arcadian hopes that launched it, perhaps that has more to do with our inflated expectations than the Web itself, says Bruce Bimber, a professor in political science and communication at UC Santa Barbara.

"So, big surprise, human nature reveals itself to be pretty much the same, even though the technologies change," says Bimber. "People behave with sort of the same mixture of crass motives and integrity online as they do elsewhere."

As Bimber, the author of books about technology and politics, points out, "One of the things that's so compelling about the Web is you find all kinds of informational strategies there." For better and worse, the Web commands our attention because it solicits our participation, even if not all its "informational strategies" fall within neat ethical lines — which is equally true of the Web's mass communication ancestors: newspapers, television and radio.

It's a feature of the Web's protean, interactive nature that duplicity and deception may be rewarded rather than reviled. When it was revealed that the witty YouTube poster Littleloca wasn't actually a teenage East L.A. Latina homegirl but a 22-year-old, non-Latina, actress-wannabe from Victorville, the hate e-mails started rolling in. But so did interest from traditional entertainment/news media outlets (including Fox, which did a long segment on the send-up), who've been sniffing around the Internet's new "stars" like hyenas circling a gazelle.

Surreptitious self-promotion, after all, is an old tool for grabbing at the American Dream, and in many circles, the attitude seems to be "no harm, no foul" — with extra points for gonzo audacity and creativity. Digital libertarians argue that the Web always has been a Wild West where rules were made to be broken and imposing restrictions could stifle free expression.

Yet some of the more devious Web stunts and manipulations raise questions about the quality of the information the Web generates and the popular culture it gives rise to. Rather than the all-access Garden of Knowledge or the Virtual Democracy envisioned by its early champions, the Web is a contested space roiled by competing claims and the pressure to stake out valuable turf. Especially as the Internet economy explodes.

When Alinta Thornton, a senior consultant on Web design and intranet applications at the Hiser Group in Sydney, Australia, wrote and posted online her master's thesis about the Web's creeping commodification in 1996, she says, "People pooh-poohed me and said, 'Don't be ridiculous.' " The prevailing idea then was that the Web would "be a public space free of interference, both from government control and commercialism" and wedded to "a larger narrative of progress," as Thornton wrote.

But like past technologies, the Web so far has proven to be no more innately pro-democracy (as opposed to merely populist) than cellphones or BlackBerrys.

"It doesn't matter what the technology is, whether it's the Internet or a horse-drawn carriage or carrier pigeons," Thornton says. "People will still lie and cheat. They misrepresent themselves to mates, they'll try to get as much sex as they can. And on the positive side, they'll try to collaborate with each other and help each other as much as they can."

Beyond the hit parade

It's that last element that leaves researchers hopeful that Web searching can move beyond sometimes bogus "popularity" to genuine originality, authority and expertise — that instead of conjuring up "The Interview With God," our future Web searches might possess a collective cognitive power that's truly divine.

Perhaps the most significant byproduct of the Web's obsession with "most this" and "most that" is the emergence of a new mass culture assembled from thousands of fragmented, narrow-cast audiences. A major challenge will be figuring out how to make that culture reflect not just the quantity but the quality of what's available via the Internet.

Right now, the Web is akin to a global, digital Miss Universe pageant in which the "most linked" and "most e-mailed" sites get the tiara, even if they won partly by sabotaging their rivals backstage. How, some researchers are asking, do you help Web surfers separate the Web's rare gold from the mass dross without imposing restrictive filters or replicating the superficial ranking mentality of the old mass culture?

Oren Etzioni, who specializes in the future of Web searching, believes that one solution is developing new models for "unsupervised information-extraction systems" that would offer search results based on a more sophisticated, composite analysis of the content of new products and services, rather than looking simply at how popular they seem to be.

"I think the fundamental motivation for a lot of the work we do is information overload anxiety. Everybody's feeling it these days," says Etzioni, a professor of computer science at the University of Washington. "It's very natural when you're overwhelmed with all this stuff to start backing away and to say, 'Hey, just give me the number, just give me my favorite source.' "

One such system called Opine, developed as part of a larger initiative between Google and the University of Washington, will take advantage of ever-more-powerful computers to sift through dozens of online reviews of, say, Los Angeles-area hotels. Then, it will develop a model of their key features, plus an overview of how these hotels have been evaluated by large numbers of bloggers, newsgroup posters and other Web users.

Etzioni, the project leader, says that Opine is smart enough to extract value judgments not just from key words but also from complicated syntax ("This hotel is ridiculously expensive"), and to organize search results to give users a more nuanced, less reductive picture of what they're looking for, accurately, authoritatively and concisely.

"The search-spam is an arms race, so it's not like Opine is an antidote to that. The arms race is going to continue. It's a fact of life," Etzioni says. But he believes that programs such as Opine will save Web surfers hours of time while also broadening their search horizons because it "is less about what site is at the top than about synthesizing information from hundreds of sites."

Given the enormous size and scope of its operations, the Web has some rankings that naturally are going to be more logical and useful than others. Google, Yahoo and other search providers are constantly tinkering with and refining their engines and algorithms, making them more sophisticated and scam-proof. The Web as a whole is busily developing more safeguards and hashing out the various legal and ethical quandaries facing it.

"We're in the early days of a whole new institution, and there are going to be loopholes," says Thornton, who compares the Web's current vulnerabilities to those of banks before safeguards such as alarm systems and surveillance cameras were developed. At the same time, she says she finds it "reassuring" that the broadly reliable Wikipedia so often turns up in the top five results for virtually any Google search, given that studies have shown most people rarely look past the first "page" of results.

Thornton is more concerned with subtler kinds of cultural biases that tend to skew Web search results, such as the continuing dominance of the United States in generating Web content and the related, disproportionate dominance of the English language. (According to some estimates, about 40% of all Web content worldwide comes from the U.S.)

She also worries about the complicity of search providers in allowing foreign governments to censor results in their home countries, whether it's the Germans barring Nazi-related material or the Chinese version of Google showing only flowery tourist images of Tiananmen Square. In the long run, she suggests, these issues will have far more bearing on world culture and freedom than whether Littleloca or one of her v-blogging rivals is pumping up her YouTube tallies.

What's needed, says Bimber of UC Santa Barbara, isn't so much a new way of policing the Web to verify its contents and make sure no one is "cheating," but "a new kind of literacy and a new kind of relation to authority." As information consumers, he says, we've been conditioned for generations to defer to putative authorities, arbiters and referees such as newspaper editors and the Federal Communications Commission.

But the great gift of the Web has been to turn millions of us from being primarily consumers into content providers and authors. While he thinks "it's a bit optimistic" to imagine the Web ever could be fully "self-policing," Bimber believes the medium could develop "pretty good self-governance," if not "definitive or authoritative self-governance."

As for the manipulation of search results or search-generated information, Bimber thinks "the best response is the outing of the practice" by bloggers and other Web users.

"Norms change slowly, and they typically require more than one generation," Bimber says. "I think we're a little bit impatient. Probably none of the people reading your article will be alive when these things are ironed out."

Etzioni, similarly, says that he's "a big believer in the idea that 'We're minutes away from the big bang — you ain't seen nothing yet.' "

"It's very early in the evolution of these tools," he says. "In 10 years — which is a huge time in 'Internet time,' as they say — we're going to have radically better tools. Which is good, because there are going to be radically more effective ways to manipulate us."

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

reed.johnson@latimes.com

http://www.calendarlive.com/printedition/calendar/cl-ca-mostviewed24dec24,0,3638211.story?coll=cl-calendar

Post a Comment